Some of my earliest and fondest memories are of listening to my grandad telling stories.

Every Sunday, we would return from the pub – the smell of warm beer, whisky and cigar smoke on our clothes – with the rest of the family, to a huge roast meal cooked by my Nana.

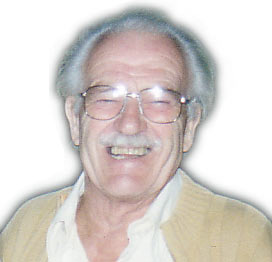

It would begin sometime between dinner and before an afternoon nap. Usually with a sparkle of Jameson’s in his smile and cheeks. One after another he would recite the poems, tales and yarns he learnt by rote as a boy, back in a craggy coastal village in North Donegal.

Stories of hope and celebration, of sailors and treasure. Tales of love lost, of broken hearts, of cruel deaths, of long departed heroes. And of migration and hunger, valour and skulduggery. I loved them all. Each and every one.

It didn’t matter to me that my grandad was profoundly deaf in one ear from an explosion back in the forties. Or that he was entirely tone deaf so that The Dubliners songs he reeled-off all had the exact same rhythm and sing-song poem-reading style without any tune whatsoever. His stories were magnetic, bawdy, rude often. He would be swept away with it all. Taking us all with him – his children and grandchildren, wrapt and encircling – he would journey to the past and to forever away …

I suppose he may be the reason why I have such a deep love for stories. From time to time, I have even been known to tell a few myself. I love that the power of stories binds and unites us. Especially when told with the practised skill of an old Irish rogue.

At around same age I also began a 15-year practice of violin playing. School taught me to play classically and with ‘correct’ technique. And how to read music score, to be conducted, and how to pass exams.

My grandad, on the other hand, gave me my love for folk music (jigs especially) with his encouragement and appreciation. I learnt to play ‘by ear’ and jam with others. The school’s violin teacher didn’t think much of my grandad – or folk music, come to think of it. But I now had a foot in each world and was the richer for it in lots of ways.

Finding a balance between the formal and informal is something I have found myself doing ever since. At 17, despite having good grades and a clean sheet, I had a moment of enlightenment and realised (for the first time), that I was in control of my own life. I walked out of school that day – half-way through the term – and changed the direction of my own life. Years later I would find myself struggling to pass A-levels. Later still I achieved a first class honours degree. When I was ready to apply myself, the hard work and application needed came naturally.

As I sit here and reflect on my journey to today, I wonder what my grandad would make of his English grandson now. What would he make of the stories I would tell him? Of the need for both a tolerance and tension between formal and informal power? And the importance of stories today more than ever in this faster-changing world?

I’d like to think he’d imagine that even an Irish peasant immigrant with a gift for storytelling and a love of life, with a glint in his eye, could have changed the world.

But I expect what would have really happened is this. He’d have poured himself another wee Jameson’s, have relit his cigar. And we’d all settle back into our chairs and each other, ready to listen to another great yarn.